Charles Lin on Urban Violence in Medieval Germany

/Charles Lin is one of the instructors who’s recent work is most in line with what Longpoint is hoping to accomplish this year. We’re pleased to present this article, which acts as a preface to his classes, just over a week away…

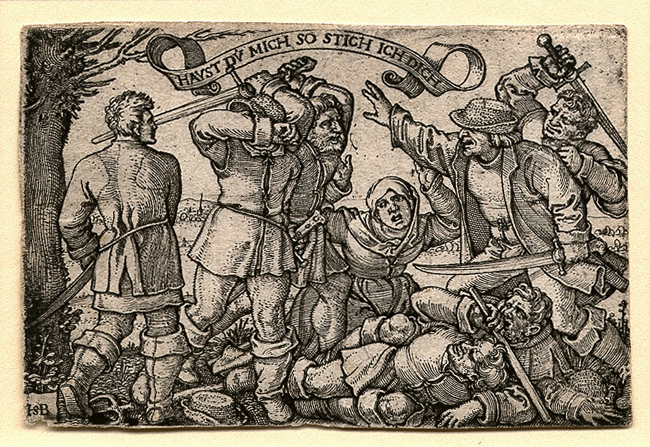

This article is about my attempts to bridge the gap between the legal and social norms of violence 15-16th c. German cities and fechtbuch techniques. I describe the contexts for urban violence in Augsburg and Nuremberg that appear in historic, non-fechtbuch sources, and introduce two scenarios designed to highlight the specific tactical problems we encounter.

Our context is a well-recognized situation throughout history. Two men get into an argument and trade insults or start shoving each other. One of the men loses his temper, draws his weapon, and tries to strike his opponent before he can defend himself.

Late medieval German cities, filled with young men nearly universally armed and with easy access to alcohol, were rife with this type of violence. In Joel Harrington's The Faithful Executioner, Nuremberg executioner Frantz Schmidt describes the day-in day-out of assaults and homicides:

...Schmidt laconically notes that a farmer stabbed a forester, or a furrier stabbed a son of the Teutonic Knights. Occasionally he makes note of the particular insult (traitor, thief, rogue), the weapon in question (knife, ax, hammer, bolt), or the source of the dispute, often trivial: for the sake of a whore over the payment for a drink; over a kreuzer; or because [his friend] cursed him as a traitor. Otherwise these accounts have the bored affect of a traffic report. In a world where men must be ever ready to defend their honor, Frantz intimates, there are bound to be accidents, as when the municipal archer Hans Hacker disarmed [another] archer's son on watch because of cursing, came to words with another and gave [the other] an accidental blow with a hammer so that he died.

...

Sudden anger, fueled by alcohol and injury (to either honor or person), sparked the violence in cases like these-- heat, as opposed to the iciness of calculated treachery.[1]

While these crimes were deemed "of passion," there were still legal and social norms that governed appropriate behavior. Ann Tlusty's The Martial Ethic in Early Modern Germany describes striking an armed opponent before he could draw or otherwise defend himself as generally considered unfair and dishonorable. 2 In fact, the act of drawing a weapon was considered a breaking the peace of the city, and Nuremberg records show a young Paulus Kal fined for such an infraction in 1449. [3]

Another incident in Augsburg in 1588, is shocking for the calculated nature of the ambush:

The Augsburg council sentenced guardsman Egidius Herman to [a lifetime sentence to fighting Turks on the Hungarian Front] in 1588 for waiting for a fellow soldier at the door of a quarter in the soldiers' barracks and attacking him with a dagger. Herman had already injured his victim, Christoph Kolder, in a fight in the quarters, during which Kolder suffered dagger cuts to his face. After companions ushered Herman out the door, he became enraged again when he heard Kolder repeatedly proclaiming in a loud voice that Herman had "stabbed him like a rogue." Waiting just outside the door to the quarters, Herman then confronted his adversary as he came out by asking, "how did I stab you?" and then putting truth to Kolder's words by sinking his blade into Kolder's chest before he had a chance to draw. [2]

According to Tlusty, "Social convention ensured that men know where the lines were and crossed them consciously, albeit at times with judgment clouded by rage or drink." Despite both legal and social norms against surprise attack, it is clear that such attacks occurred with some frequency. So how does one construct scenarios that faithfully replicates the uneasy balance between legal and social norms, social honor, and/or alcohol for the 15th century burgher when choosing which social and legal lines to cross?

We don't.

We are modern people, in a modern time, and trying to simulate the social decision to cross certain norms of violence, in a different country, in a different time, is likely to end in folly. Instead, our scenarios focus on how the legal and social norms of the use of arms shape the tactical problems that practitioners of Kunst des Fechtens and related arts might have faced.

This context for violence thus inspires two scenarios we will explore at Longpoint. The first scenario, called “Quick Draw,” recreates a “cold” ambush – two people, an Attacker and a Defender, stand at handshake distance, weapons sheathed, in casual stances, when the Attacker suddenly draws their weapon and tries to kill the Defender before they can draw. This scenario not only examines situations that don’t begin with overt conflict, but also gives practitioners the opportunity to explore the mechanical skills associated with drawing their weapon and beginning a fight from a position of unreadiness.

The second scenario, called “Bar Fight,” recreates a “hot” escalation – two people are physically shoving or striking each other and throwing insults, when one suddenly loses their temper, draws their weapon, and tries to kill the other before they can draw. Using a special setup of referees and signals, we can make the transition from unarmed to armed conflict unexpected for the person who is being drawn upon. This setup allows us to explore the tactical problem of the unexpected transition to armed violence, without recreating the social decision to do so.

In testing these scenarios internally, we have found that the proximity of unarmed conflict alters the shape of armed techniques, and that the threat of armed violence alters the shape of unarmed techniques. Techniques from Nuremberg Group treatises and Lignitzer appear most appropriate for the types of tactical problems our “self-defense” scenarios present. Ringen skills are extremely valuable - not just because of the close range of these scenarios, but also because ringen principles and techniques allow a person to gain advantages without crossing the legal and social norms against drawing a weapon in anger.

Although this post describes a “class” at Longpoint, I view it as an exchange of ideas. Although we have insights to share about how these scenarios inform our understanding of some sources, these scenarios may offer you independent insight or interpretations into your own practice that I would love to hear, and I look forward to exploring this with you all at Longpoint 2019.

[1.] Harrington, Joel. The Faithful Executioner. 2013. p. 153.

[2.] Tlusty, Ann. The Martial Ethic in Early Modern Germany. 2011. p. 96.

[3.] Die Nürnberger Ratsverlässe, Band 1, Irene Stahl, Degener, 1983.